How do you say ‘white as snow’ in a place where people have never seen snow?”

Linn Boese, WorldVenture missionary and Hebrew exegete living in Cote d’Ivoire, West Africa, posed this question to me as we chatted about the challenges of communicating the gospel to people in a completely different culture and in a language that’s not written.

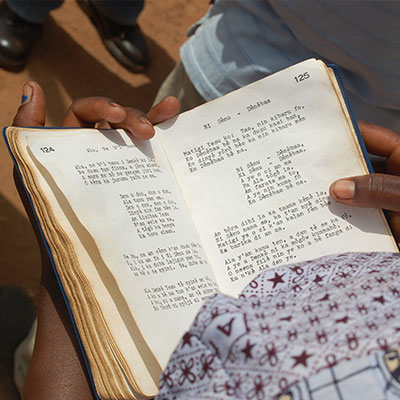

That’s right, the Nyarafolo language, spoken by more than 60,000 people in the country’s northern villages, was not written down until Linn started her literacy project.

For more than 20 years, Linn has been at the helm of a unique Bible translation project in the previously French-colonized Cote d’Ivoire, where she is leading efforts to preserve the Nyarafolo language—all in the hopes of bringing people to the gospel. Her efforts have caught the eyes of the National Ministry of Culture and of those scattered to other regions, as the Nyarafolo people discover that their language is written down.

“It’s a very rich language,” said Linn. “In order to make [the Bible] meaningful or understandable, you often have to change the way things are phrased…but you also are keeping the naturalness of the language in the translation so that it will be acceptable and heard and understood.”

Looking back a few hundred years, it’s arguably the Bible translators—William Tyndale, Martin Luther, Erasmus, and others—who activated the explosive spiritual rebirth of the Reformation. Tyndale, who translated the New Testament into easy, monosyllabic English, had equal or more influence on the English language than William Shakespeare.

Erasmus once wrote:

“Christ wishes his mysteries to be published as widely as possible. I would wish even all women to read the gospel and the epistles of St. Paul, and I wish they were translated into all languages of all Christian people, that they might be read and known…I wish that the husbandman may sing parts of them at his plow, that the weaver may warble them at his shuttle, that the traveler may with their narratives beguile the weariness of the way.”

In many ways, WorldVenture’s Bible translators are following in the footsteps of Reformers who risked and gave their lives for syntax and grammar. Translators—perhaps more than most missionaries—are lovers of language. And language, going all the way back to the time of Babel, is inextricably linked to culture, so much so that those who strive to understand the complexities of language are striving ultimately to love people better.

Modern Reformers

In Senegal, Diibril came to Christ through missionaries who came to his fishing village. He learned how to read Wolof, and began reading the Wolof New Testament, which WorldVenture missionary Marilyn Escher has been a part of translating since 1972. Diibril’s family rejected him, as he was the only Christian in a family following folk Islam. Now he lives in a Wolof farm village, doing development work in a community garden, sharing his faith as best he can—thanks to the Scriptures he can now understand.

Baboucarr* and his wife Kaddy* are from two different people groups in Senegal, so their common language is Wolof. They use the Wolof scriptures for reading their Bibles together as a family, which propels them into serving 29 street children with food, medicine, and clothing.

These are just two brief examples of the influence Marilyn has had on the lives of the Wolof people through the Wolof translation project. Although interested in translation from a young age, it wasn’t until after majoring in linguistics and meeting other missionaries that Marilyn decided to commit her life to it.

“I had a great peace in my heart; I have no regrets, to be so intensely in God’s word every day,” she said.

Among the Wolof people, where nearly 100 percent are Muslim, Marilyn’s work is somewhat comparable to Reformation translators. Because the Qur’an is written in Arabic, which the majority of Senegalese do not speak, they rely on their imams to explain and teach the deeper truths of their holy book, as was the case for Europeans when only the Latin Bible existed before the Reformation.

For Marilyn, she cares about getting the word of God into Wolof so they can understand it for themselves. And in a country where only one-third is literate, WorldVenture’s Steve Newkirk is publishing audio recordings of the Wolof translation for those who cannot read.

“Women are not encouraged to go to school,” said Marilyn. “With the translation, we’re wanting to reach the illiterate and especially women.”

WorldVenture missionary and translator Thomas Requadt, along with his wife Laura, moved to southern Mali in July 2003 after a forced relocation due to the rebels taking over their home in March 2003 as a result of the the Ivorian civil war which broke out in 2002.

There, as in Côte d’Ivoire, Thomas is working on a translation project, also in a highly Muslim context. With threats of the Islamic State looming over parts of West Africa, he finds it all the more urgent and necessary to equip the believers in southern Mali with the Bible in Shempire.

“That’s the need for the translation,” said the Requadts. “When things go south, they’ll have God’s word so they can go directly to it, something that speaks right to the heart, using their mental concepts.”

For all these translators, working in Muslim or animist contexts has meant a focus on the Old Testament, as the background story of the fall of man and the need for an ultimate sacrifice is paramount. For Marilyn in Senegal, it’s important that they publish Wolof scripture editions in Arabic lettering as well as Roman lettering (also a free app in the Google Play Store), with beautiful Arabic-looking borders to accompany and make the words appealing.

Marilyn said that while Muslims commonly believe in the idolatry of Christians for worshipping three gods (the Trinitarian view) and for thinking God become a man, moments of clarity come to the surface during the Bible translation verification process. A Wolof man who had studied the Qur’an for seven years was working on Daniel 3, the account of the four men in the fiery furnace.

“Who do you think the fourth man was?” Marilyn asked him.

After thinking for a minute, the man responded in an astounding way: “Maybe God, protecting them.”

Evangelical Outreach

The misconceptions surrounding Bible translators often revolve around an image of a frail missionary bent over a typewriter in a dark room, tediously converting biblical truths into a remote language spoken in the middle of the jungle. It’s seen as an isolating, dry, uninteresting task that only the most dedicated labor their whole lives to accomplish.

In reality, many of these missionaries organize and lead teams of local translators during their projects, relying on native Wolof, Shempire, and Nyarafolo speakers to accomplish the initial drafts often with help from the missionary in understanding the text in the original language. They then take these drafts and have them translated back into French so outside consultants can check the translation. Before the consultant arrives, Marilyn and Linn have their teams take the draft out into the community to read it to people representing different facets of society, checking for clarity. During the actual translation verification with a consultant, some who are bilingual (in the translation’s language and French) come to help check the text, telling the consultant what they heard when it is read to them.

In other words, these translators are engaging in evangelical outreach. Linn recalls one Muslim man who was helping her team verify the Gospels. Near the end of the project, the man proclaimed, “This is really dangerous. You could want to maybe even be converted to follow Jesus if you kept listening to this.”

Katelynn Boardwell, a short-term translation worker and daughter of WorldVenture missionaries in Ireland, served for two months with the Nyarafolo translation team. She recalls one Muslim man from the community who was doing the back translation of the book of John.

“I was praying that God would soften his heart and show him His truth,” Katelynn said. “The book of John is so explicit about how you’re saved, and how Jesus is the one who gets you to heaven, that I was praying he would have an open mind.”

Several times, the man would pull back from the table and sit with his head in his hands. When he came to John 14 and read how Jesus is “the way, the truth and the life,” he again pulled back from the table and didn’t say a word. On the last day of his project, the man said he wanted to come into the kingdom of God.

“The word of God is powerful,” said Katelynn. “Linn told him we had been praying for him the whole time.”

For WorldVenture workers devoted to these translation projects, this is the whole goal. It’s not just about linguistics, but about offering people the opportunity to read and wrestle with the word of God as they have never heard it before.

“We’re not just there for the linguistics; we want to use linguistics and Bible translation in order to make disciples and plant churches,” said Thomas in Mali. “That’s what we’re all about: seeing people transformed by the gospel.”

It’s no surprise that the tedious nature of Bible translation requires hard work and dedication, but just as it sustained Tyndale and others before them, it’s also no surprise how a firm belief in the lost state and sin of humanity spurs them onward.

“People have no hope without Jesus,” said Linn. “They are enslaved to a system that impoverishes them, that takes away their liberties, and Jesus is the only hope.”

How to Get Involved

Go:

If you are feeling God’s call for you to step out in faith and improve literacy and Bible understanding for the purpose of church planting, visit www.worldventure.com/go and talk to one of our coaches about opportunities in each of these places, as well as many others.

Pray:

Pray for WorldVenture Bible translators and their national partners in West Africa. Pray their hard work would be fruitful and result in making more disciples among the Wolof, Nyarafolo, and the Senofou people. Pray for more leaders to be called to Bible translation for the sake of those who have yet to have the Bible in their own language.

Give:

WorldVenture translators are in need of more funds to ensure getting the Bible into the hands of local Africans. Please consider visiting www.worldventure.com to give to these efforts and more.